Bethlem at Beckenham and the Scottish Village Asylums by Dr Gillian Allmond Part Two

See Part One of this blog here

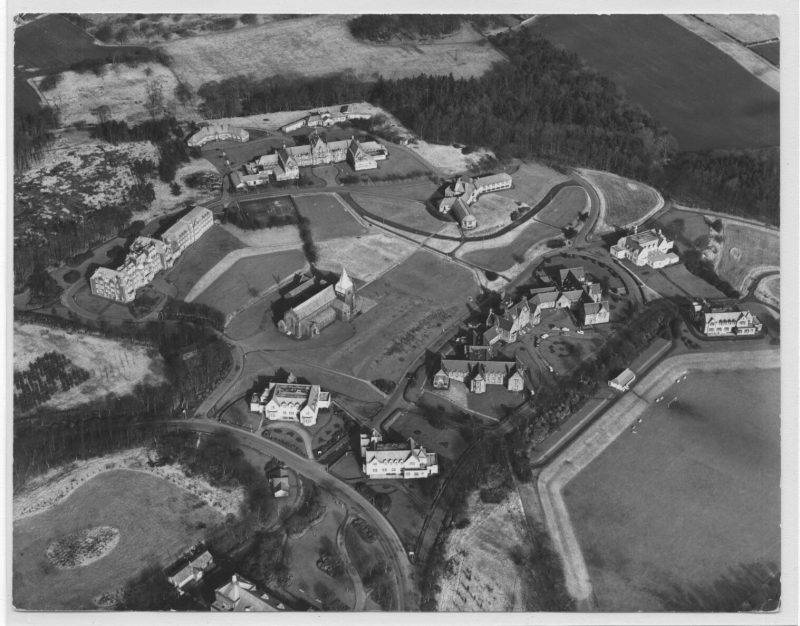

Aerial view of Bangour Village Hospital in the 1990s, reproduced by kind courtesy of Lothian Health Services Archive, Edinburgh University Library

At the end of the nineteenth century, Scottish asylum authorities were inspired by Alt-Scherbitz, near Halle, which offered one of the most innovative asylum regimes in Europe. Following the visit to Alt-Scherbitz of Scottish Lunacy Commissioner, Dr John Sibbald, Edinburgh and Aberdeen District Lunacy Boards and Crichton Royal Asylum also sent delegations to see Alt-Scherbitz for themselves. The architect for Purdysburn, Belfast, was another who paid a visit before producing his designs. The asylums that were subsequently constructed on rural estates outside Dumfries, Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Paisley (Renfrew) and Belfast varied in their fidelity to Alt-Scherbitz as a model. Aberdeen and Edinburgh appear to have had no perimeter fence or wall, but Renfrew did, for example. However, all five asylums housed the majority of their patients in villas, even, in some cases, those who were quite severely affected, and many of these villas are very successful in conveying the style and scale of suburban dwelling houses.

The new asylums were variously praised by contemporaries for combining the ‘advantages of the home and of the labour colony’ while being ‘as free as it is possible for an institution to be from the prison-like appearance and depressing environment which in popular conception are inseparable from a madhouse’[i]. The freedom and ‘avoidance of everything suggestive of restraint such as enclosing yards’ at Bangour was noted, as was the lack of formality or regularity in layout. The villas at Bangour were ‘treated with such variety of form and environment as to destroy all appearance of official residence’.[ii].The Medical Superintendent of Purdysburn emphasised that more complete classification of patients would be possible and also pointed to the ‘hygienic efficiency’ of the villa colony where each villa had maximum access to natural light and fresh air.[iii]

Although the colony asylums were generally well received, there were critics among both medical professionals and architects. Some pointed to the extra expense of supervision in separate buildings. More fundamentally, others doubted that mentally unwell patients had the capacity to appreciate the ‘home-like’ feel of the village asylum.[iv]

The resemblance of some villas to stylish middle-class homes was too much for some observers. In an extraordinary, possibly alcohol-fuelled, outburst at the formal opening of Bangour Village, former prime minister, Lord Rosebery, complained that the villas were ‘sumptuous homes for the insane … laid out as daintily as they could be for the blood royal’ and asked rhetorically ‘why do all this for the intellectually dead?’[v]

This is a sharp reminder of the low status of the poor and mentally ill at this period and it is this kind of criticism that may explain why the colony design was rejected south of the border in the decades before Bethlem. A proposed colony based on the Alt-Scherbitz model at Whalley in Lancashire was dropped after six years of planning in 1906 because the design was judged to be more costly than a conventional asylum and there was ‘no clear proof’ that there would be any benefit to patients. [vi]

[i] Journal of Mental Science Vol 50, pp.471-490

[ii] The Builder, 10th November 1906

[iii] Allmond, G. (2018) ‘Levelling up the lower deeps – rural and suburban spaces at an Edwardian asylum’ In: G. Laragy, O. Purdue and J. Wright, eds.. Urban Spaces in Nineteenth-century Ireland. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press

[iv] Blanc, H.J. (1908) ‘Bangour Village Asylum’ RIBA Journal, XV (10), pp.309-326

[v] Lord Rosebery on the insane and their cost’ The Lancet 2 (27 Oct), pp 1160-1163

[vi] Allmond, G. 2017 ‘Liberty and the Individual: the colony asylum in Scotland and England’ History of Psychiatry, 28 (1), pp.29-43

Plan of Bangour Village (Edinburgh) Hospital

One advantage of the colony design that was sometimes highlighted was its flexibility. When numbers of patients increased, as they continued to do in the early twentieth century, more villas could simply be added to the ‘village’. In this way, many of the village asylums continued to grow, much as a genuine suburban settlement might do. Today, Purdysburn and Renfrew continue to provide psychiatric care, although some of the older buildings are now vacant. Smaller-scale buildings can also more easily be repurposed. Bangour Village is sadly derelict, but many of the buildings are listed and planning has been sought for residential redevelopment. Developers at Kingseat have converted some of the old villas into housing, the design clearly lending itself to this kind of reuse, while Crichton’s ‘Third House’ has been converted to a different kind of institutional grouping in a park-like setting - a university campus.

It is not entirely clear whether the architect of the new Bethlem, Charles E Elcock, was aware of the Scottish precedents for the type of layout used at Bethlem but it is possible that these were an influence for him. A drawing assistant of his, John Manuel, had also been assistant to the architect of Bangour Village Hospital. However, Bethlem is a product of the cultural aesthetic of the 1920s and 30s rather than that of the Edwardian period, and perhaps of changes in attitudes to mental illness. Rather than being ‘domestic’ in style, and resembling suburban villas, the accommodation blocks at Bethlem evoke the architecture of hotels or sanatoria, prioritising access to air and sunlight, rather than ‘home-like’ appearance. The regular grid pattern of the site also contrasts with the meandering pathways of the Scottish village asylums. However, in claiming this new site for ‘modernity’, Bethlem did make a decisive break with the past in England - the days of the towering and terrifying Victorian asylum were over.

Aerial view of Bangour Village Hospital 1960-1975, reproduced by kind courtesy of Lothian Health Services Archive, Edinburgh University Library

Villa at Dykebar

Dr Gillian Allmond is a Visiting Scholar at Queen's University, Belfast. Her recent PhD thesis (forthcoming BAR Publications 2021) was an analysis of the architecture and interiors of village and colony asylums in Scotland, Ireland and Germany and she has several publications on this topic. Gill is currently working on a commemorative project for the 175th anniversary of the famine in Ireland and is also researching the development of 'open-air treatment' in Britain and Ireland at the beginning of the 20th century. She welcomes interaction with interested individuals or groups and can be contacted at [email protected].