Change Minds Online 2022: Frederick Herron by David Luck

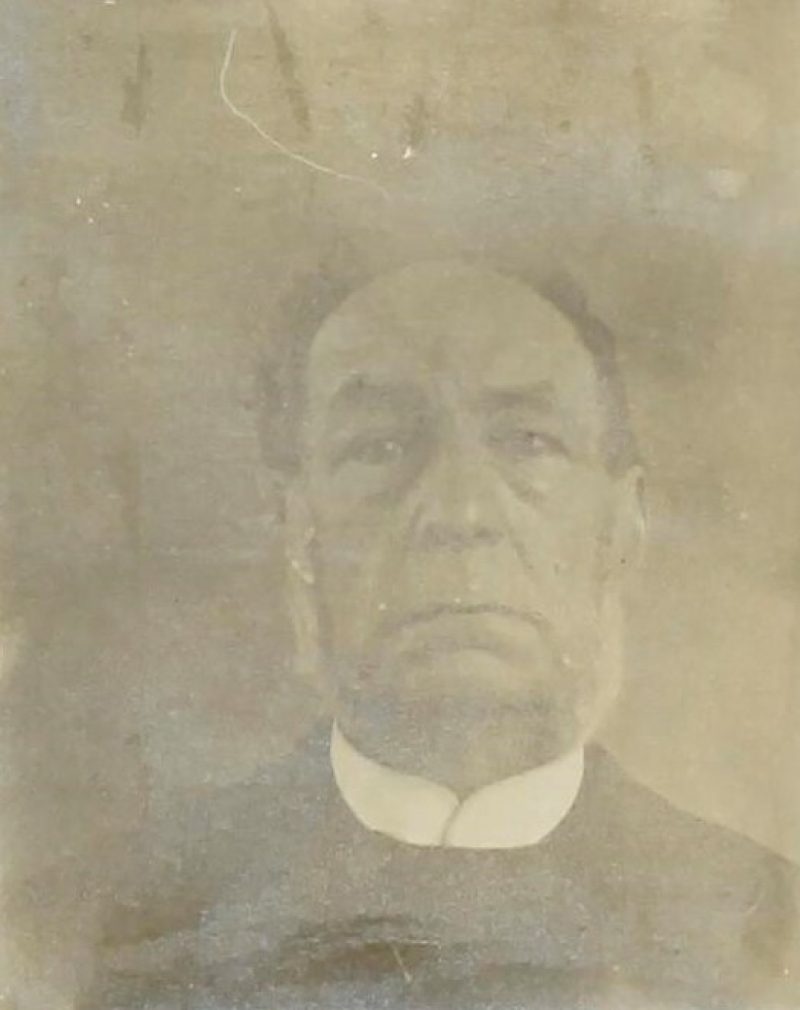

Frederick Herron taken from the 1888 Bethlem Hospital casebook

Frederick Thomas Herron was born in Stoke Damerel, now a suburb in Plymouth, in 1817, the son of David and Mary Herron. It seems likely that his father was a storeholder, himself the son of David and Rachel Herron and baptised in Charles the Martyr, Plymouth in 1792. Herron is an uncommon surname in Plymouth, and so it is relatively easy to identify Frederick and his family- it may well be that his grandfather was a mariner from the north-east of England or Scotland who settled in the city, or that Herron was a corruption of ‘Herrin’, a family name possibly from Exeter. Frederick grew up with two sisters, Rachel Matilda Herron (born 1821) and Amelia Jane Herron (born 1823).

After Frederick’s birth David is subsequently listed in various records as a baker and as a grocer. Mary, sometimes listed as Martha or Mary Hay, died in 1832 and David remarried to Catherine Hall in 1833 at Charles the Martyr in Plymouth. The family’s address is given as Paradise Row in Stoke Damerel on Mary’s burial record, and David is listed there as a storeholder in the 1827 Tourist’s Companion to Plymouth. Clearly his business, which he probably operated at the same building as the family home, was permanent enough to be listed, but he was never profitable enough or owned enough property to be included in the rates books or electoral registers.

David passed away on 15th December 1850 and was buried in Stoke Damerel (his address given as 15 Paradise Row), but by that time he seems to have given his children a start in life. Rachel Matilda got married to a draper, William Braddon in 1843 and Amelia was married to Charles Gideon Edwards, a jeweller whose father was a gunsmith, in 1848. Interestingly in both marriages David is described as a ‘gentleman’, therefore a man of means without employment. This may imply that at some point in the early part of the decade he had managed to retire. Frederick’s Bethlem record hints at a darker truth, as Grace Herron describes her grandfather as having become ‘paralysed’.

In the 1841 census Frederick is not living with his family, but is instead lodging with the family of John May in Chapel Street in Devonport, another current suburb of Plymouth. Both men are listed as ‘chemists’, and it seems likely that this arrangement was a way of Frederick learning a trade from the older man. In 1843 Frederick got married to Mary (possibly formerly Mary Kipling, but I can’t find proof of this in the parish registers), who is listed in various census entries as the same age as Frederick or up to three years his junior. In the 1851 census they are living together in 76 West Street in Plymouth with their 6 year old daughter Grace and their three year old daughter, Lucy, though their middle daughter Jessie (born 1846) seems to be staying at the Braddon’s, at least on the night in question, which was half an hour’s walk away. Even though Frederick had probably only been running his own business since just before his marriage he has an assistant, Frederick Gribble, in the house, and two servants, a general house servant and a nurse maid.

The nurse maid was there to look after Frederick’s youngest child, Frank, then barely a toddler. Frank died in 1852 at the age of two. Frederick and Mary’s second son, Alfred, also died relatively soon after his birth in 1857. They did not have any further children.

Despite this, Frederick enjoyed a successful career as a chemist and druggist. He moved to 4 East Street. In the 1871 census Grace, a governess, and Jessie are still living with them, together with an assistant druggist and a house servant, implying a prosperous business and a comfortable standing in society. Lucy is herself working as a governess for the family of Thomas Bulteel, a banker in Stoke Damarel near the family home. Frederick also lived with an apprentice to his trade, which probably reflects his standing in society. His shop was regularly listed in trade directories and guide books, and he crops up as a name witnessing wills and other legal documents, implying that he was a respected presence in the business community in Plymouth. He was also listed in electoral registers, something that his father never managed. This meant that Frederick owned enough property to qualify. Curiously this property doesn’t seem to have been his own house and shop until the 1870s, but was instead a patch of land to the north of the city that seems to have been a speculative holding, and a share of the hotel.

In a letter attached to the casenotes Frederick recounts that his mind became ‘excited’ following losses suffered by his investments in trams and other stock companies. This may well refer to the collapse of the Plymouth, Devonport and District Tramways Company, who failed in their objective to build a steam tram network in the City centre in the early 1880s. According to Frederick, this meant that he had to sell everything to appease his creditors, leaving him with nothing. His letter, addressed to the doctors at Bethlem, appeals for the Hospital to take him on as a permanent patient, and stresses that he and his wife and daughter (Grace) are without regular income and will starve.

The letter is undoubtedly written in a distressed state, and how much of it is true is debateable. The Hospital probably kept it because it reflected the depths and the development of Frederick’s delusions, but the part about losses rings true, if to a exaggerated degree. In his admission records one doctor records how Frederick complained that he did not have a penny to his name and the next minute pulled sovereigns from his pocket. Grace herself is recorded as stating that while he had suffered financial woes, he (and her and Mary) had sufficient means. Indeed, even Frederick later acknowledges that Grace and Mary were lodging in Holloway while he was in Bethlem (confirmed in the admission register as 43 Carleton Road, Tufnell Park, in what still looks like a spacious Victorian townhouse).

By the time he came into Bethlem in September 1888, Frederick had sunk deeper into this depression, believing that both Grace and Mary were dead and that he was going to become destitute. Clearly, the strain of supporting his family without a son to pass his business on to, and whatever he had lost of his investment, had triggered something within him. One of the doctor’s notes records how he could become violent when he wasn’t allowed his way, and had broken his wife’s arm in a struggle. It is also striking to the modern reader how Frederick repeatedly emphasises that he has no family and friends to help him, when the records that survive seem to implicitly contradict this.

In the Hospital the Bethlem doctors recorded that Frederick began believing himself to be inhabited by a sloth or another animal, and that this ‘spirit’ was slowly taking him over. He seems to have been obsessed about his lack of clothes as well, and these delusions were still in place up until May 1889. Perhaps in response to this, and his own worries about his financial predicament, the Hospital extended his stay by three months in August 1889. They then allowed him a trial period of leave before discharging him ‘relieved’ in December to his wife and daughter.

Relieved meant that the doctors did not believe Frederick was yet well, but that he had recovered enough to continue outside the Hospital. Sadly their caution was correct. The last note in the case books dated April 1890 records that Frederick has made a personal application to the Guardians of the Poor at Plymouth to be looked after, and that he suffers from ‘frenzies’, though he was not readmitted to Bethlem.

Interestingly, the Hospital and Frederick do not mention his other daughter, who was not dependent upon him. Jessie was married in 1874 to Thomas Samuel Stevens, a mariner whose father was a shipbroker. In 1891 there is a Jessie T Stevens living in Islington with her son Frank H. Stevens (age 15) and a daughter, Barbara P Stevens, not far from where her sister and mother were when Frederick was in Bethlem. By 1901 they have moved to Hampstead, and Frank is described as a solicitor. I can’t find Thomas’ death, so I would suggest that he may have been at sea during the census times. The family seem to have had enough income to employ a servant at their homes, which were in fashionable locations and large houses. Perhaps she could have supported her father if needed.

Mary passed away in 1895, Frederick in 1898, both back in Plymouth, though presumably not at East Street, which had other occupants in the 1891 census. I cannot locate any of the family in the 1891 census, which perhaps indicates that they went abroad to try to help Frederick.

In the 1901 census Grace and Lucy are living together in a lodging house in Phillimore Place in Kensington, and are described as ‘of independent means’- which again seems to imply that Frederick was able to leave them some sort of living. Lucy dies in Kensington in 1923, Grace in Kensington in 1930. However Frederick’s name was continued by Frederick Herron Edwards, the son of his sister Amelia born in 1863. Like the original Frederick, FH Edwards seems to have had a successful business career, as a gunmaker like his father, and owned several properties around the Plymouth area by the 1900s.

Artwork

My frustration with researching Frederick is that while there seems to be moments of extreme loss and sorrow in his life, especially with the death of his sons, what survives to us are records of his business, and his relative success with his chemist. It is a sad irony that his perception of failure in his profession also became the medium through which he experienced and expressed his mental health issues.

My artwork tries to reflect the domination of his druggist business in the records we have of Frederick counterpointed with the deeply troubled man we see in the casebook. To do this I created a repeating collage of an image of chemical bottles on shelves (taken from a photo of Bethlem’s own laboratory) with my own pen drawing of Frederick’s case photograph. This is the first drawing I have tried for at least 15 years, and I was surprised and happy with the effort, and I feel it captures more of the man in the Hospital than the research I did into his wider life.

I hope Frederick found some peace within himself in his last years.