Change Minds Online: William Charles Chard part 1 by Dr Nick Hervey

Photograph of William taken in Bethlem by Barker and Parker 1887-1888, reproduced from glass plate negatives in WUC-04

The first admission

William was first admitted on 30th July 1887 from his home at 15 Algernon Road, Hendon on the Authority of his wife, Amelia Arabella Chard. He was said to have been ill for 5 months before admission to Bethlem. One of his sureties was a neighbour at No. 11, the Lock Manufacturer, Charles Douglas. The other was James Bishop, a neighbour from 8 Wilberforce Road, the other side of the Railway Line. It seems the Bishops may have become friends, because by 1891 James and his wife Emily, and their 8 children, had moved to Algernon Road.

William was recorded as a former Clerk to the British Medical Association, raising questions as to whether his illness had contributed to his being unemployed at this stage. The family were Church of England, and William was said to have sober habits. It was recorded that he had three children, but with no details, aside from that the youngest was just 2 years and 7 months old.

The first medical certificate was signed by James Cameron, their 39-year-old G.P. who lived nearby with his wife and three sons in Church Lane, Hendon just over a mile away. Cameron qualified M.D.C.M. from Aberdeen meaning he was Medicinae Doctor et Chirurgiae Magister, a doctor of medicine and master of surgery, qualifying him for general practice. He deposed from personal observation at interview that William looked wild and was excitable. William told him that he couldn’t work because he got muddled, and that he wouldn’t go to his job because while he was out his wife’s brother, Henry William Honiball, would frequently come to the house to have immoral intercourse with her. The G.P. also noted that William told him he’d been going to work ‘of late’, although he knew for a fact that he hadn’t gone there for at least two and a half years.

Under the heading ‘Facts communicated by others’, Dr Cameron noted that William’s wife, Amelia and his sister [probably Mary Louisa ,who lived with them subsequently] reported that he was easily aroused and had periodical episodes of excitement. In addition to constantly accusing his wife of immorality with her brother, he had threated her with a knife once or twice, and imagined that ‘a brother steals his boots’.

The second certificate signed by James Edward Bottomley, confirmed the outbursts of ungovernable rage, wild looks, and accusations of adultery, but added a loss of memory and the use of filthy language, including when the children were present. He also elicited from the wife, sister, and lodger, Mr Buxton, that William had threatened to murder his wife.

Once admitted William had a work-up from the house surgeon, based on information provided by his wife. Lately he had been rather irritable, but had always been very fond of his children. He had been teetotal for over 25 years and had never been ill before. The section on supposed cause of his onset remained blank, although the death of his father Valentine Joshua a few months earlier might have merited a mention. His reaction to questions was good, and despite the threats to his wife, he was not considered homicidal.

Medical staff were worried by his very poor recent memory and impaired remote memory, and given this and his pronounced sexual delusions, the provisional diagnosis queried whether he was developing General Paralysis. Against this, his features were healthy and his walk and reflexes were normal, although his weight of 10 stone 10lbs, was quite low and could have suggested the start of some emaciation, consistent with General Paralysis.

Almost immediately William began to suggest that he had made too much of his suspicions about Amelia and her brother, and the doctor recorded that he, ‘was inclined to hedge concerning his delusions.’ He then tried to rationalise them, by suggesting that he’d made these accusations, ‘because he did not want her brother at the house,’ and that he didn’t believe, ‘there was any truth in what he said.’ When asked, he was consistently wrong about the year, and also about the length of his admission. After 2 months he still retained his ideas about Amelia, but after a further two months of ‘no change’, it was reported in December that he had grown fat and was generally working in the garden. This continued on into February, and on March 7th his time at Bethlem was extended for three months.

On the 28th he was given leave of absence for a week, and for the two weeks after that the week’s leave was extended twice. This evidently went smoothly, and he was discharged well by certificate on April 18th 1888, after an admission of eight and a half months - returning home to his wife and children. There was no mention of the fact that in addition to the death of his father not long before his admission, his mother had also passed away in December 1887, half way through this admission, which in all probability meant that he missed her funeral.

The second admission

On the face of it this was a successful admission, but in March 1889 just over a year later William started to relapse, and was eventually readmitted on 26th September 1889. It seems likely on this occasion that the family had taken the decision to protect Amelia from being the one to decide on William’s admission, given his delusional ideas concerning her, although, somewhat strangely, given his beliefs about him, it was Amelia’s brother, Henry William Honiball, under whose authority William was sent. On this occasion it was two relatives, rather than neighbours, who acted as sureties - Amelia’s father, the butcher, Henry James Honiball, and her older sister Henrietta’s husband, John Samuel Pallant, a Surgical Instrument Maker.

Once again their G.P. James Cameron signed the first medical certificate, and the second was completed by Dorset born Charles Henry Augustus Stone, who lived at 1 Neeld Terrace, The Hyde, Hendon. He was a Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh and of the Society of Apothecaries and had been practising for 17 years, since 1872. He was also just coming out of a traumatic divorce from his wife Hannah Elizabeth Tooney Stone, in which he had been cited for adultery, and lost custody of his three children to his wife.

Once again William was not considered suicidal or dangerous which is surprising considering the certificates provided by Cameron and Stone. Cameron noted that William’s personal care had deteriorated and he was filthy in his habits – going about in a ragged condition. He once again asserted that his wife was unfaithful and, in addition to her brother, was having improper relations with her father. He also gleaned from Amelia that William had threatened to stab her with a knife and that she went daily in fear of her life. He had also accused her of immorality in front of their daughters aged 11, 7 and 4, and repeatedly used filthy language.

Stone provided a variant of this in his interview. He reported William as saying his wife prostituted herself, and that his brother-in-law ‘came also daily to have connection with his wife and steal his books.’ He also reported that William had threatened Amelia with a pistol, as well as a knife. He too noted that Amelia went in fear of her life.

In a similar pattern to the first admission William very rapidly began to back-track on the accusations he had made. The doctor’s notes record that rather than his relapsing 6 months before this second admission [as recorded in his admission details] in March 1889, he had in fact only remained well for four months after his discharge in April 1888 – suggesting that he had in fact been unwell for closer to 11 months before this second admission.

One new fact elicited, although it is unclear its relevance, was that one of his brothers had an alcohol dependence problem. Staff also recorded that William had been knocked unconscious by a beam of wood some 12 years earlier, again probably irrelevant to his mental health problems. Something which was different was the level of verbalised threats. When told about a possible re-admission he had threatened to commit suicide if he was taken in, and had also said to his wife that he would murder her, and then wouldn’t be hanged because he was a lunatic. At this time he frequently went wandering from home, sometimes for several days, a not uncommon feature of delusional psychosis, and a new feature of his delusional system was that he believed his beef tea poisoned.

It is unclear if William’s threats were designed to control his wife’s behaviour but during this relapse he had acted in a very controlling manner, refusing to let his wife out of his sight. At times after accusing her of unfaithfulness, he would say his accusations were false, but then soon after return to them. Doctors recorded that he had gradually developed a perfect hatred for her, the children and other relatives. He was generally sleepless, a common effect of emotional disturbance, and would talk most of the night, disturbing his wife’s sleep.

When questioned William denied that he ever meant to carry out any of his threats and recognised that his ideas were false. He said he loved his wife too well for that. He also said that his wife’s brother used to call every day and spend hours at the house, which whilst aggravating his delusional ideas, was perhaps understandable, as the Honiball family must have been worried for Amelia’s safety, and her father was not a well man at this time [he died in 1891].

The doctor’s report describes rather expressionless features, not uncommon in the middle of an episode of mental psychosis, and a nervous manner, possibly owing to his fear of another long admission. The doctor also recorded that William seemed to have no idea of the seriousness of the charges he was making against Amelia’s brother. Once again his memory impairment was noted, but in the absence of physical tremor or emaciation, but there no longer any suggestion that this was General Paralysis.

One week after re-admission he regretted, ‘deeply ever having made base accusations against his wife. Knows that they are delusions and is sure that if he got out he would treat his wife properly.’ He was again eating and sleeping well and had ‘rather’ taken to life in the hospital and wasn’t, ‘particularly anxious to go out.’ From this point he seems to have recovered and on New Years Day 1890 had his admission extended by 3 months. On the 4th February he went to Witley Hospital for a period of convalescence, returning on April 15th, and was discharged relieved the following day. There is no trace of William’s time at Witley, except for a general report by the Lunacy Commissioners from the year before which shows that as in Bethlem, the 12 men and 18 women were managed separately at Witley, and aside from concerns about the fire safety precautions, the feedback from patients was complimentary about the care they were receiving, and Charles Philips reported the medical officers visited frequently.

The problem with dates

William’s first admission stated that he was 36 years old, which initially appeared to match up with information from the census returns which suggested he was born in 1852. Strangely his second admission, two years later, stated his age as 34. He had apparently got younger. So many recorded dates in the Census and in official records are incorrect that the only reliable source is the original baptism record, which in many cases also shows the date of birth, often added in an extra column of next to the baptism date. Baptisms varied hugely in relation to birth details, and often older children in a family were baptised together with much younger siblings. On William’s St Giles, Holborn Baptism Register entry his baptism date was given as 19th October 1851. In a far column a birth date was originally entered as 14th September 1851, but subsequently amended to 14th April 1849. So his true age on first admission was 38.

What the admission didn’t tell us - the family story

Bethlem recorded that William had three children but with little or no details. The first thing to say is that both William and Amelia had been married before [see William’s own family tree]. On 21st June 1877 William had married Ellen Brockley, at St Thomas Church, Agar Town, in the St Pancras area where almost all William’s family and relatives came from. Sadly Ellen died on 7th March 1879, some 5 and a half months after giving birth to Ellen Isabel [Nellie] between July and September 1878. Amelia Arabella Honiball, William’s second wife had herself been married on 16th December 1873 to a Henry Hook, a 21-year-old warehouseman from St Pancras. His father, also Henry Hook, was a butcher in the St Pancras area, and as Amelia’s father, Henry James Honiball, was also a St Pancras butcher, it seems likely that this is how the couple had met. Henry was 21 and Amelia 19 when they married, but Henry died 4 years later leaving her a widow at 23.

So when Amelia married William on 13th June 1880, she also took on his 22 month old daughter, Ellen Isabel. The couple subsequently had two daughters of their own, Grace Mary Amelia Chard on 25th December 1881 ,and Ethel May Chard, on 1st December 1884. Thus at his admission he had three daughters aged 9, 5 and 2½.

In 1880 William [31] and Amelia [26] were both still relatively young to be entering a second marriage, but they both had close extended families. Looking at the bare bones of William’s two admissions recorded at Bethlem leaves one with the immediate feeling that there was little hope for their future together. He had had two longish admissions (8½ months) and (almost 7 months), which featured strongly held delusions about his wife having sexual relations with her brother, father and unnamed others, combined with some alarming threats to kill his wife with a knife or gun, and a deterioration in his memory and self-care.

Yet, as the various census records and probate return shows the couple went on to live together for 36 years until William’s death in 1926. They obviously had some means of income as the 1901 Census shows them living at Hambledon, 34 Sandycombe Road, Twickenham and William is returned in the Occupation column as Own Means.

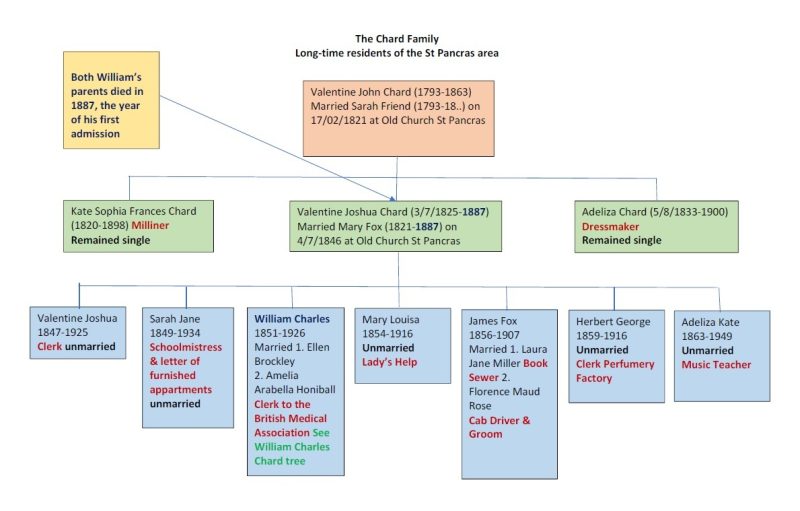

William's family tree

The three children

For part two of Nick's research please go to https://museumofthemind.org.uk/blog/change-minds-william-charles-chard-part-2-by-dr-nick-hervey

To see more on Change Minds Online you can find more blog entries here or you can see the exhibition of all our participants' creative work via our page here .