Hospital Snapshots 10

Observable evidence was thought to be crucial in documenting changes and determining recovery so drawings and later photographs could be valuable tools. The case of Eliza Ash provides a good example of the type of noticeable change that might suggest progress. There are three drawings of her, made when she was a patient at Bethlem in the 1840s suffering from mania, with brief comments added by Alexander Morison.

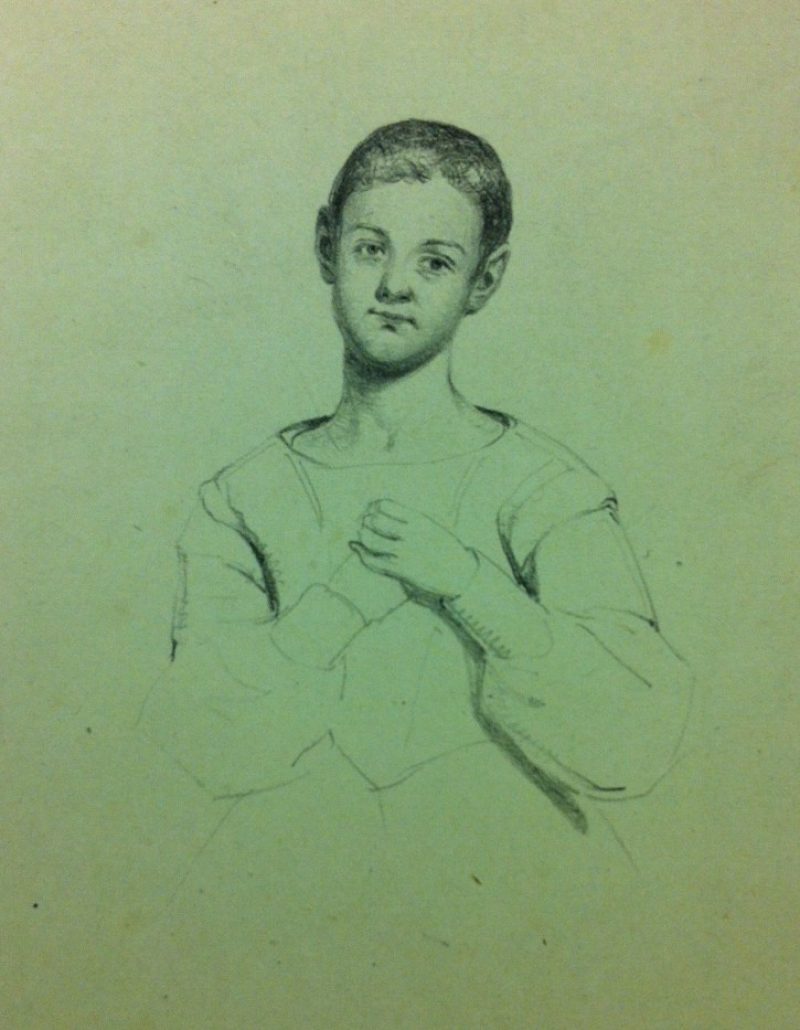

Though some details are similar, she does not look at the artist in any of the drawings for example, some change in Eliza is visible. On her admission she was said to be ‘violent and mischievous, with incoherence of speech’ and the first drawing was made when she was in this state. We have a clear view of her face; her head held at a slight angle so that she is looking down and off to the side. Her mouth is closed but her lips are not pressed together to denote any tension. Her oval face looks longer due to the cropped hair which sits close to her head, well off her forehead, cut round her ears so that both are visible. The overall impression is perhaps of someone lost in their own thoughts.

It is not clear if Eliza is standing or sitting but she has her arms raised and clasped loosely at chest height. Much of her dress is visible but, as is typical with the drawings, it is merely sketched in. It has a high scooped neck unadorned with any type of collar, quite a full skirt and full sleeves which are narrowed to a cuff at her wrist.

In the second, Eliza is seen in a three-quarters profile. She appears at some distance from us. Her face is rounded and well filled out though the chin is quite defined. Both eyes are visible. She has short styled hair that partially covers the ear. Some, at the rear, appears to be longer or to have come loose and is trailing down her neck. Her mouth is closed. She appears open and relaxed, almost as if she is inwardly smiling, though perhaps at something only she is privy to.

Eliza is wearing a loose fitting dress, not much more than the scooped neckline visible. The impression is of someone sitting rather than standing, perhaps with her hands in her lap. Her posture betrays some tension, the shoulders a little hunched.

In the final picture, Eliza appears to be nearer to us, we see her more clearly. The three quarter profile is sharper; on the right only the eye lid and lashes are visible. Everything about the image is more defined; the face has lost some of its roundness, the eyes wider and clearer, the nose more shapely. Once again, the mouth is closed. Her hair, though similar to the first picture, is slightly shorter, revealing the whole ear. It is styled more elegantly, the line perfect.

Eliza’s dress appears more fitted, darts at the front are hinted at. It is trimmed with a narrow white band at the neck. Her body language gives her more of a dynamic air and the impression is one of someone standing with arms at their sides or perhaps loosely clasped in front. This final picture lends her more personality than the first, though arguably she conforms to the nineteenth century ideal of female normality. Everything in it seems to be pushing us towards the conclusion that we only have to look at her to see that she is convalescent.