James Hadfield, The French Revolution and the Redefinition of Insanity by Sophia Gal: Part One

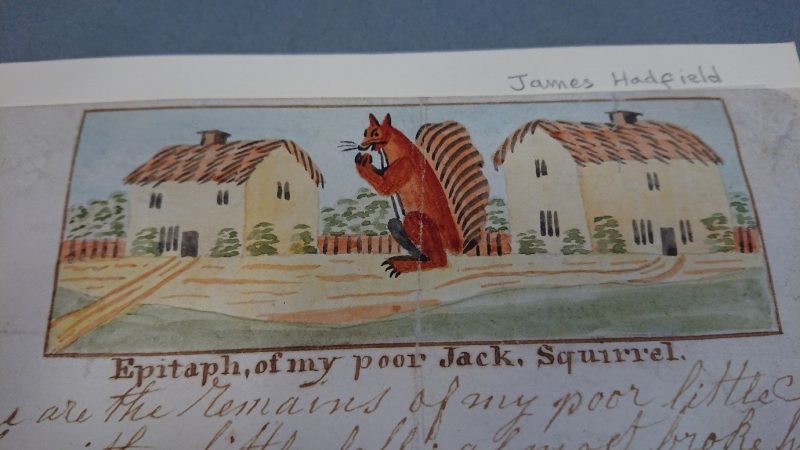

If you have paid a visit to our permanent exhibition, you might have seen Epitaph, of My Poor Jack, Squirrel, penned by Bethlem detainee James Hadfield in 1826.[1] However, beyond Hadfield’s lamentation for his animal friend is the story of a man who would inadvertently transform the legal perception of insanity beyond recognition.

[1] James Hadfield, Epitaph of My Poor Jack, Squirrel I, 1826, Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

Epitaph, of my poor Jack, a squirrel by James Hadfield, one of three versions held at the Museum

Insanity and Mens Rea

Before Hadfield’s trial, those who successfully pleaded insanity were acquitted. In certain cases, a special hearing could be had, but the rules of these hearings were vague. Some criminals were sent home to their families, some confined in hospitals, and some even chained to the walls of churches. To be acquitted, defendants had to prove that they were completely unable to distinguish good from evil, which kept the standards of insanity narrow.

Before the 1740s insanity pleas were very uncommon. It is suspected that they increased because of the industrial revolution and the way it dramatically changed societal structure. In the 60 years that followed, there were 100 insanity pleas at the Old Bailey, over half of which resulted in acquittals. This cast a shadow of doubt over the effectiveness of mens rea.[1]

The issue of the innocence of insane criminals was brought into the 18th-century public eye by the attack on Lord Onslow by Edward Arnold. By common consent Arnold was insane, but his attack was planned methodically, meaning that he knew exactly what he was doing. The legal precedent, as stated by Lord Justice Kenyon, was that to be legally insane a man must be “totally deprived of his understanding and memory, and who does not know what he is doing any more than an infant, than a brute, or a wild-beast."[2]

Thus, understanding his condition was a challenge, let alone applying legal judgement.[3]

[1] Richard Moran, “The Origin Of Insanity as a Special Verdict: The Trial For Treason Of James Hadfield (1800)”, Law & Society Review 19, No. 3. (1985) p. 487-519.

[2] Valerie Agent, “Counter-Revolutionary Panic and the Treatment of the Insane: 1800”, Studymore, last modified 1978, last accessed June 9, 2020, http://studymore.org.uk/1800.htm.

[3] “High Treason”, Bell’s Weekly Messenger, June 29, 1800.

The Assassination

On May 15th, 1800, Hadfield visited Drury Lane Theatre. The King of England, George III, was also in attendance. When the king rose for the National Anthem, Hadfield fired his pistol towards the Royal Box where the king stood. This act was witnessed by three musicians, who dragged Hadfield over the rails into the music room where he met the Duke of York. Hadfield said to the Duke, “God bless your Royal Highness, I like you very well, you are a good fellow. This is not the worst that is brewing.” Hadfield held the Duke of York in high esteem because he had served under him as a dragoon as well as a bodyguard and had fought on his behalf in Flanders.[1] When they saw the attack, audience members cried out "Secure the villain!" To which Hadfield replied, "I believe I have secured him safe enough.”[2]

[1] Thomas Bewley, “Madness to Mental Illness: A History of the Royal College of Psychiatrists”, Royal College of Psychiatrists Online Archive 17, accessed June 6, 2020, https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/about-us/library-archives/archives/important-legal-cases-of-the-19th-century-james-hadfield.pdf?sfvrsn=e4cedf57_4.

[2] “High Treason”, Bell’s Weekly Messenger, June 29, 1800.

The Trial

On June 26 in court, Hadfield was represented by Thomas Erskine, whose 1779 testimony against the corrupt Lord Sandwich - among other speeches - had placed him in very high esteem.[1] It was there that Hadfield confessed that he was entirely aware of what he had done - thus failing the ‘Wild Beast’ test - but that it was not his intention to harm the king. “I was tired of life,” Hadfield stated, “and my plan was to get rid of it by other means. I did not mean any thing against the life of the King: I knew the attempt alone would answer my purpose.” Instead, the ‘purpose’ Hadfield referred to was to be trampled to death by the crowd so that he may not “[d]ie by his own hand.”[2] Hadfield believed that he was fated to die just as Jesus had [3], and that his sacrifice would bring about the Second Coming of Christ.[4] The Duke of York was also present at the trial, and Hadfield said to him that he knew he would be killed for his transgressions but did not care, telling him once more that the worst was yet to come.[5]

This was not the first of Hadfield’s acts of derangement. His sister-in-law testified that he had attempted to kill his eight-month-old son on the grounds that God had told him to do so. Charles Price, a fellow soldier, stated that Hadfield attempted to stab him in 1796 in Croydon. Perhaps the most telling of all was the account by John Lane, a private who was with him in hospital, who said that Hadfield believed himself to be George III and would search his head for a golden crown.[6]

The explanation for this, according to the medical professionals present at the trial, was the four sabre wounds to his head, that were inflicted on him while fighting in Lisle. Surgeon Henry Cline asserted that at least three of the wounds were enough to cause brain damage, and that this effect would be irreversible. Dr. Creighton, a physician, had no doubt that Hadfield was insane and that his injuries were the cause.[7]

[1] William Pannill, “Thomas Erskine: Lawyer for the Ages”, Litigation 27, No. 2 (2001) p. 53-59.

[2] Richard Moran, “The Origin Of Insanity as a Special Verdict: The Trial For Treason Of James Hadfield (1800)”, Law & Society Review 19, No. 3. (1985) p. 487-519.

[3] “High Treason”, Bell’s Weekly Messenger, June 29, 1800.

[4] “High Treason”, Bell’s Weekly Messenger, June 29, 1800.

[5] “High Treason”, Bell’s Weekly Messenger.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Richard Moran, “The Origin of Insanity as a Special Verdict”.