Neurology, the “Unconscious” and Victorian Psychiatry

The copy of Theo Hyslop’s 1895 publication, Mental Physiology in the Wellcome Library was, presumably, originally the doctor’s own, as it is interleaved with reviews, calling cards and letters to Hyslop from other mental health professionals, forming a fascinating archive in itself.

Mental Physiology was written mainly for the psychological part of Hyslop’s London M.D, which he completed while working as Assistant Medical Officer at Bethlem. Hyslop’s successor, William Stoddart, found it “strange” that the book never reached a second edition.1 Perhaps Hyslop’s efforts to associate somatic and psychological theories of mental health and illness did not integrate easily with a growing divide between neurological and psychotherapeutic approaches. Nonetheless, Mental Physiology certainly shares similar evolutionary concerns with much British psychiatry of the period, in emphasising the importance of volition (or will) to both the individual and broader civilisation, simultaneously associating mental ill-health with a loss of, or failure to attain, this self-control.

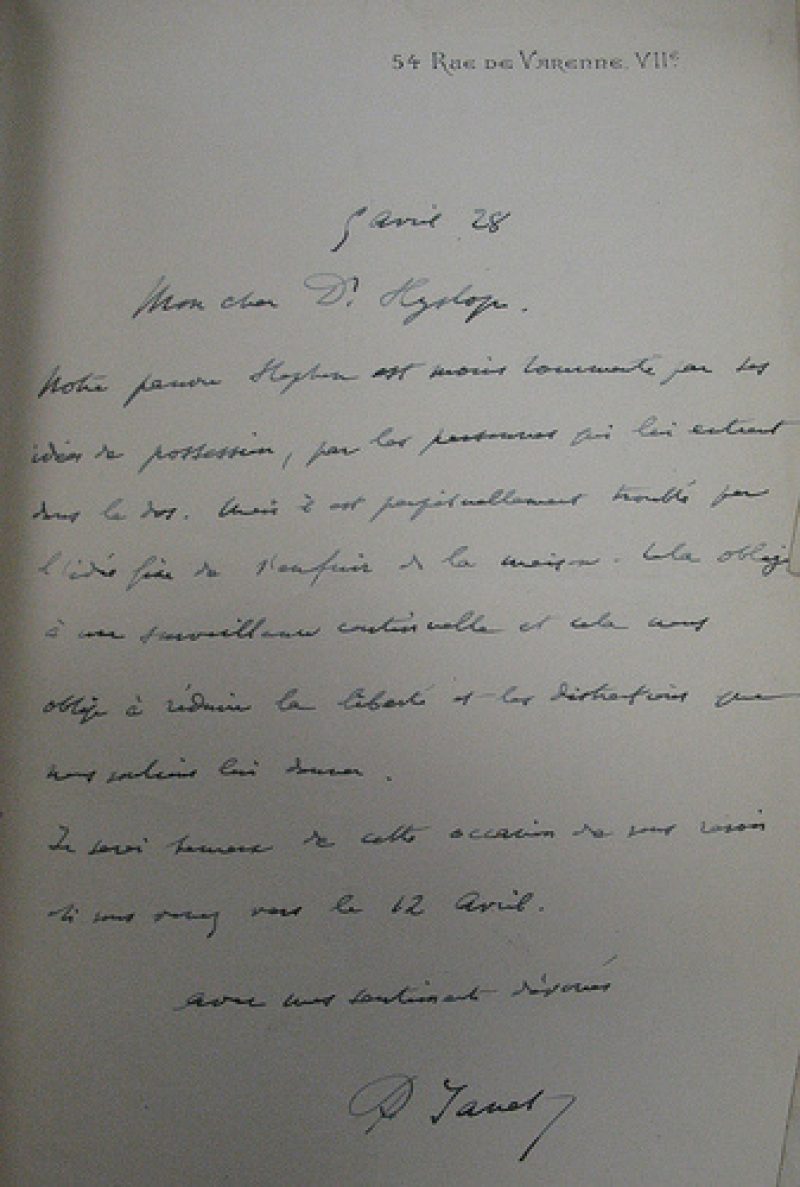

Hyslop was also heavily influenced by French neurology, much of which stemmed from the work of Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpêtrière in Paris. Mental Physiology contains numerous references to the writings of Charcot’s pupils, such as Charles Féré and Pierre Janet. Janet is of particular note here: his calling card appears among the numerous psychiatrists’ cards pasted into this copy of Mental Physiology (from physicians across Europe and the United States), presumably received when they either visited Bethlem or attended a conference or meeting of the Medico-Psychological Association. A letter from Janet to Hyslop, also included in Mental Physiology, would seem to be part of a longer correspondence between the two, for it discusses the symptoms, and treatment, of a particular individual, presumably known to both parties. Since Henri Ellenberger’s research into The Discovery of the Unconscious in 1970, Janet’s work has been regarded as important in the formation ‘dynamic psychiatry’ and psychotherapeutic techniques, through his explorations into repressed memory, multiple personalities and the connections between past events and present trauma.2 It is interesting to see here evidence of an established link between French and English psychiatry during a period in which, according to the traditional historical view, continental ideas had limited influence in England.