'Queering the narrative' in the archival records at Bethlem Museum of the Mind

‘There were numerous gay psychiatrists who remained mute on the subject of homosexuality, such as Edward Mapother (1881 to 1940), superintendent of the Maudsley Hospital from 1923 to 1939’

Edward Shorter, A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry (2005, Oxford University Press) p.130

Edward Shorter drops this unfootnoted and otherwise unevidenced remark into his historical dictionary of psychiatry to illustrate how psychiatry has struggled to explain and to deal with non-heterosexual relationships in its history. As we look back, it very much appears to us now that the professional judgement that same sex attraction was a medicalised issue represented a grievous overreach by psychiatry that caused very real harm to healthy people. It also represented an attitude that persisted until relatively recently, as even in the DSM III, published in the early 1970s, ‘homosexuality’ was listed as a psychiatric disorder.

But the remark also illustrates the issues if we try to research and publicise a diversity of sexual orientation in the field of mental health. Even if same sex attraction and relationships were not pathologized and stigmatized, would we know if someone in the historical record was gay? Mapother himself was married for many years, and there is nothing in the small collection of his personal papers we hold about his personal feelings on the matter. At the Museum we do not look to pathologise long dead service users or staff with today’s medical language, and it feels like a double standard to try and ‘out’ people's sexuality when all we have are unsubstantiated rumour and interpretation.

Perhaps then what we can do is look and see evidence of a broader spectrum of sexual attraction and behaviour than the normative heterosexual behaviour that we expect in history. – what historian and writer Justin Bengry calls ‘queering the narrative’.

We know from the Bethlem casebooks that the people receiving treatment in the hospital came from a wide range of ethnic, cultural and class backgrounds, and so it would make sense that there would be a range of sexualities. From recent work undertaken by our archive volunteer, it seems that after the First World War the Hospital recognised same sex attraction in the language it used, and while it can’t be said that the language or use is particularly positive, it is at least surprisingly non-judgemental in the instances we have found.

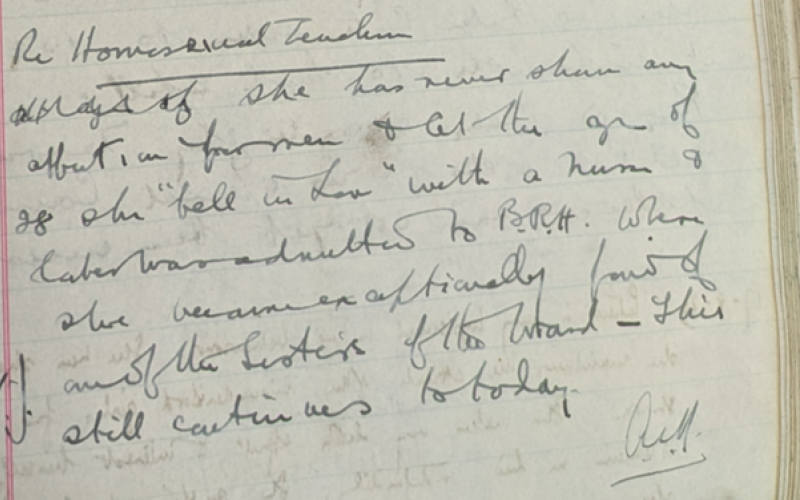

Maurice Emery, admitted in 1920 suffering from depression and fears of persecution, was described by doctors as showing ‘homosexual tendencies’, and by his father as having ‘one or two boyfriends’ that he was ‘enthusiastic’ about. It’s quite possible that this was the reason Maurice felt alienated from his family, but though Maurice’s sexual preference is noted it is not pathologized or viewed as a cause of his mental health issues. Grace Bowen, admitted to Bethlem for a second time in 1920, was described as having ‘homosexual tendencies’, but as these seemed to manifest with her ‘neurasthenia’ and manic conduct, and was directed to ‘the sisters of the ward’ the Hospital seems to have been unsure whether this was part of her life or a feature of her illness. Her brother could only add that she had ‘never shown any affection toward men’, and recounted the circumstances of her earlier admission to Bethlem.

Extract from Grace Bowen's 1920 record about her 'homosexual' tendencies.

The detail that surrounds Grace’s behaviour on her first admission in May 1913 is much less clear. There she is reported as having fallen in love with her sister’s nurse, whom she then followed around, and apparently threatened suicide when challenged on this. Other than this threat, there seems little evidence of what we would recognise as a serious mental health issue, and the Hospital records relatively little detail in her patient progress notes, other than her smashing crockery on a period of leave in her parent’s house where she lived. There is only silence in the casebook as to whether Grace was suffering from a mental health issue, or if she was a young woman showing understandable frustration and anger at being denied love by her family. It seems to reveal that at this point in time same sex attraction was alone enough to justify the seven months she spent in Bethlem.

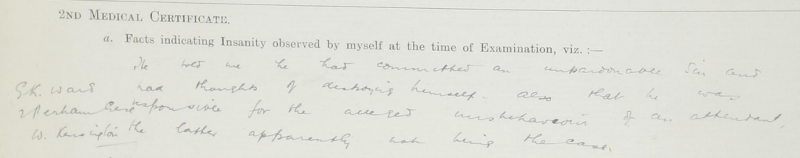

We can also compare the relatively ‘open’ language of the post-War period to some of the innuendo and coded language of the Edwardian Hospital. What, for example, was the ‘unpardonable sin’ that Charles Branscombe, an artist’s assistant also admitted in 1913, thought he had committed, and what was the misconduct by an attendant that he was responsible for? It’s possible that there is a sexual element to this, or it is possible that there is not- however it does seem that the truth hides behind a kind of coded language being used, and that perhaps there lies a greater knowledge once we decipher that code.

There seems to us to be much work to be done in this field before we can understand and explain the lives of those in our past. We’d be very interested in hearing from, or facilitating this sort of research into the casebooks- please do get in touch.

Extract from Charles Branscombe's case record that mentions his 'unpardonable sin'