Change Minds Online 2023: Richard Kettle by Amy Moffat

What first drew me to Richard was the stylised writing of his name in the record. It felt a strange choice for a medical entry, and I couldn’t help but think about the person who would have made that entry. Were they creative? Or perhaps just bored? Unfortunately, I will probably never know who it was that entered his name with such flourish, which was good practice for letting go of the unknown when researching Richard’s life.

Richard was baptised on 22 January 1868 in Grandborough, a small village just outside of Rugby, to Robert (b.1833) and Sarah Dorothy Kettle (b. 1838). His family seemed to be deeply religious; he was baptised by Rob Kettle, a potential grandfather, and his own father later became the Rector of Lidgate, Suffolk. The first time he appears in the census is in 1871, where his family are guests in Rectory House, Little Bardfield, Dunmow, Essex. Richard had a big family; we see his oldest brother John, (b. 1863), alongside Robert Harry (b.1864), Mary H R (b.1865), and Edith (b.1870). Later came Florence (b.1873) and Ernest (b.1877).

He next appears in the records in 1881, away from the family home in Lidgate. We see him living at 61 Montpellier Road, Brighton, under the care of Sophia Lombe White, head of a preparatory boys school. A bit of digging shows that Sophia founded Marlborough House School in 1874, which now exists as a preparatory school in Hawkhurst, Kent. Described as a “stern Victorian lady with a heart of gold,”[i] the school had basic facilities, with rigorous cleaning schedules for both the building and the children. It would have been a very strict environment and I wonder what room was left for kindness, and if there were any lasting impacts on Richard. Not long after 1881 he went to Lancing College, which he left at the age of 13 due to becoming depressed. His mother told Bethlem doctor’s that he was “slow at learning but very persevering,” and managed to attend a day school after being treated by a doctor for three years.

It appears Richard’s adult life was very unsettled. He was an apprentice in London between 1888 – 1889, and he enlisted, first in the 5th Lancers and later the 1st Dragoons at the age of 21. Both of these enlisting’s didn’t last very long, and at some point in the 1890’s Richard embarked on the long journey to Australia, which in that period could take at least two months. According to his hospital records Richard had gone to Australia because of a pain in the head, though they were keen to note that it was “not really a pain in head – but feelings.” Whilst there, about five months before his Bethlem admission, he had become “maniacal” and had returned home for treatment. It appears he might have received home treatment at first, but three weeks before his admission to Bethlem started to experience hallucinations, slept poorly, was weak and violent.

On his admission (February 23, 1892) he was delirious, tired and weak. His rambling conversations indicated anxiety and fear – although largely incoherent, one phrase the doctor’s could pick up was “don’t shoot me now!” Richard was first placed in a padded cell, in which he was constantly displaying restless movement. The clinicians remarked on his physical ill-health and his poor diet and noted that the only way to get him to eat was to be fed via a tube. Throughout the rest of the month and into early March we don’t see much change – he is still sleeping poorly, experiencing hallucinations, displaying restlessness at times, and is incoherent in speech. The doctors are clearly concerned about his physical ill health; they keep track of his temperature, which appears as a mild fever, and his pulse, which they note was weak. By March 6 we see a marked improvement – he is taking food well and appears to look healthy, though his speech is shaky. We are then given only short notes – “altogether better,” “to Witley,” until his final discharge (“discharged well”) on May 25. It would be tempting to think from this short stay at Bethlem and rapid improvement that Richard’s illness was a physical one from which he recovered and never looked back. However, what I have found out about his life after Bethlem shows a lifelong history of mental illness.

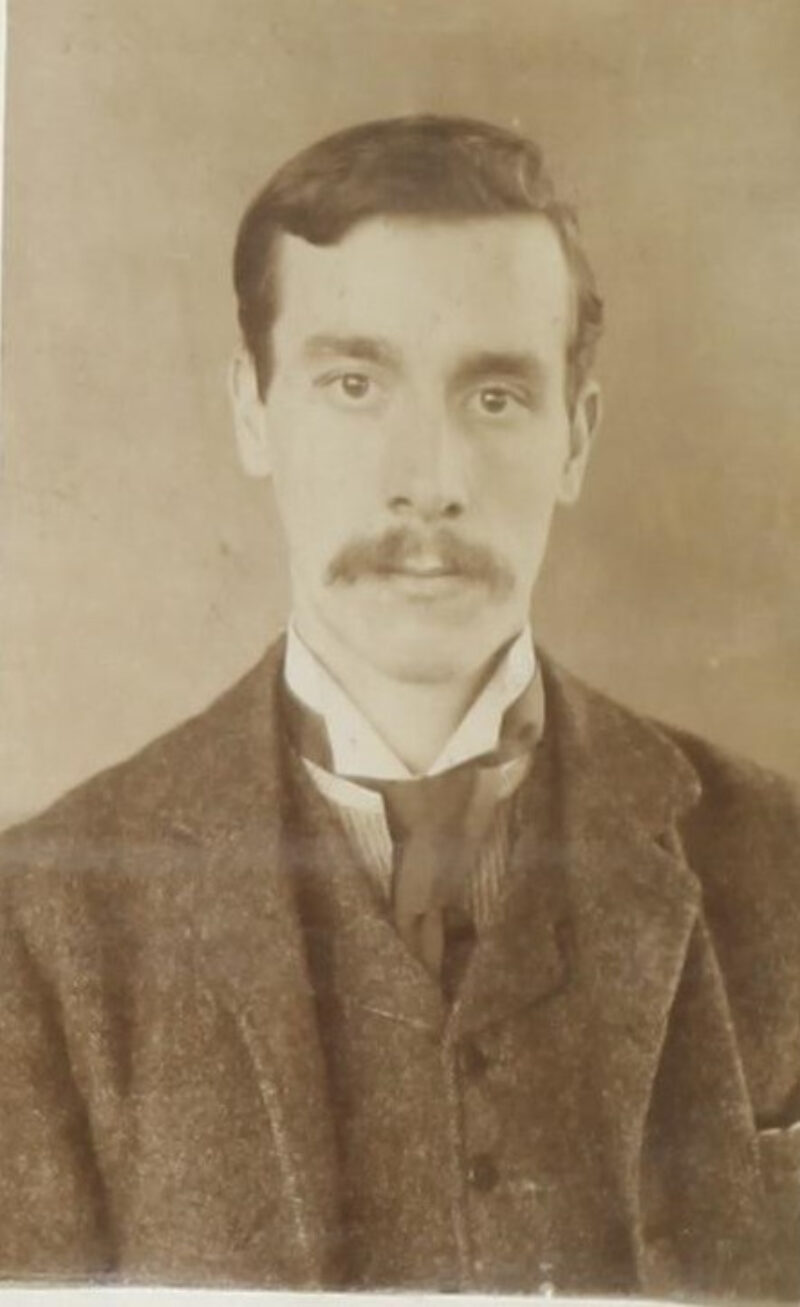

He next appears in the record in Holloway Sanatorium, a relatively new asylum at the time located in Virginia Waters, Surrey, which opened in 1885. He was admitted on 18 May 1893 and discharged 7 May 1894. This is followed by many years in and out of Holloway – admitted as a voluntary border in 1900, certified there in 1902 and discharged “recovered” in 1908. Some of the Holloway records have been digitised and made available on the Wellcome website[ii], and incredibly within those we have a photo of Richard taken almost 11 years after his time in Bethlem. It is recognisably Richard – he is wearing the same style clothes, and though the hair on his head is a little bit thinner, his moustache is a lot fuller. However, he looks very tired and perhaps a little bit more guarded than his photo at Bethlem.

From then we start to lose Richard in the record – the last time we see him is in the 1911 census, once more in Holloway. However the Holloway records for that period onwards are closed, so we don’t know how long he was there for. I have been unable to find any other definitive records for his life that point onwards – there is a grave in Australia for a Richard Kettle, b.1867 in England, which could be possible as we only know that Richard was baptised in January of 1868. This Richard died 1 September 1944 at the age of 77. Frustratingly he has no listed family or birthplace on his death certificate, so we can’t know for certain if it is him. Curiously he is in the Dane family vault in Springvale Botanical Cemetery, Victoria, which also contains the remains of Dr Paul Greig Dane – one of Melbourne’s leading psychiatrists, credited with being a pioneer of psychological treatments in Australia and, though not a psychoanalyst himself, founding the Melbourne Institute for training of psychoanalysts[iii]. It’s tempting to think that Richard left the UK for Australia and was able to find a place for himself there, perhaps forming a bond with the Dr Dane. Although we might never know for certain if it is the “right” Richard, I want to imagine that this is how he lived out his last years; building meaningful relationships, in a country he loved, amongst those who truly cared for him.

[i] https://www.marlboroughhouseschool.co.uk/history. We can also see that one of Richard’s fellow students, George C Brooke, lost his life in World War One.

[ii] https://wellcomecollection.org/works/s3pqejg4

[iii] https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/196890668/paul-greig-dane

what we wear

During my research I saw two photos of Richard Kettle – one taken at Bethlem in 1892, and one at the Holloway Sanatorium in 1903. He is wearing almost the same clothes in both, but in the second photo he looks much more tired and guarded. Richard found himself in and out of Holloway for at least 15 years between 1893—1908. I thought about his experiences in both institutions, about what he was carrying with him, and decided to represent this through a collage made up of images taken at Bethlem and Holloway, arranged to resemble his outfit in the photos.